May 27, 1973 Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: Allman Brothers Band/Grateful Dead/Waylon Jennings/Jerry Jeff Walker (Sunday) Bill Graham Presents--canceledThe biggest rock concert in American History was the "Summer Jam" at Watkins Glen Grand Prix Racecourse in Watkins Glen, NY, where 600,000 fans saw the Allman Brothers Band, the Grateful Dead and The Band perform on July 28, 1973. Three-quarters of those fans got in for free, however, as the crowd overwhelmed the fences.

The highest paid attendance at any concert was the next Spring, at Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario, CA, 35 miles East of Los Angeles on April 6, 1974. 200,000 or more fans fans, at least 168,000 of whom paid, saw Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Deep Purple and The Eagles headline over a slew of other popular bands.

Yet on

Memorial Day weekend in 1973, on Sunday May 27, Bill Graham Presents had

booked the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers at the Ontario Motor

Speedway. It would have been the first show at the Speedway, and the

first time the Dead and the Allmans had been booked together since the

Fillmore East in 1970. The show was abruptly canceled, almost certainly due to tepid

ticket sales. Yet the paired booking and the venue would prove to be the

biggest winners in the history of rock. What happened?

This post will review what we can determine about Bill Graham's grand

plans for the Ontario Motor Speedway on May 27, 1973, and why he was too

early.

|

Winston Churchill ca. 1946

|

Winston Churchill was famously reputed to have said of his decisions in World War 2 that "History will be kind to me, as I intend to write it." It is largely forgotten now that the perpetually-broke Churchill made his living as a best-selling author of history books, so this was no casual assertion. [For the record, Churchill's actual quote was

"For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all

Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write

that history"]. Giant figures in rock music, notably Bill Graham, implicitly took Churchill's adage to heart. Graham is widely viewed as the greatest rock concert promoter in the 20th century, a view widely promulgated by Bill Graham. It isn't untrue, by the way--it's just that Bill made sure that the entire rock world heard his version of events first and loudest.

Bill Graham's modern twist on Churchill, however, was not as an author but as an interview subject. Graham gave more interviews than perhaps all rock promoters put together, always had a great story, told them well, and never told a provable lie. Sure, sometimes he favored his own interpretation of events. Every journalist and rock star biographer told Bill Graham's version of the story, and the very best of Graham's practices and innovations--and there were many, to be sure--took front and center, cementing Graham's legacy forever. Rock History was indeed kind to Bill Graham, but he was instrumental in the composition of that history.

In the Spring of 1973, Bill Graham took a big swing in the Southern California rock market, planning to put on the biggest concert in regional history. He struck out, massively. He never mentioned the event again, not in a meaningful way, and the story disappeared. In retrospect, Bill actually looks pretty good: he was absolutely right about everything, but he was just a little bit early. But that wasn't the story he wanted to tell, so he didn't tell it. Only the bare outlines remain.

Rock Festivals and Major Rock Venues: Status Report early 1974Rock

Festivals were a product of the 1960s.

Gina Arnold's excellent 2018 book

Half A Million Strong (University of Iowa Press) tracks how "free shows in the park" evolved into

"giant multi-day events in some farmer's muddy field" over the course of

a few years (yes, she's my sister but you should still read it). By the

time of the biggest festivals of 1969 and 1970, most famously

Woodstock, hundreds of thousands of people would come to some outlying

area and camp out for several days, while live rock music blasted 24/7.

Legendary as these events were, most fans did not attend more than one

giant event, and most communities that endured a huge rock festival did

not tolerate a second one.

The live rock music business got bigger every

year, and various efforts were tried to find a way to have "festival"

events on a large scale. Multi-act events were appealing to promoters

because they inherently hedged risk in a volatile music market. Since

shows had to be planned many months in advance, it was hard to

anticipate how one band might have a breakout hit, and how another may

have become over the hill, or even broken up, in the few short months

between booking the show and playing it. In early 1969, for example, Led Zeppelin found themselves playing tiny auditoriums, sometimes as the opening act, with their debut album roaring up the charts, while at the same time Vanilla

Fudge found themselves no longer the draw they had been the year

before. A rock festival, with dozens of acts over a few days, could more

easily absorb the hits and misses. Promoters continued to search for a

way to book multiple acts profitably.

|

An aerial shot of the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Course on July 28, 1973, with some of the 600,000 fans in attendance at the Allman Brothers/Grateful Dead/Band rock concert

|

Rock Concerts at Auto Racing TracksThe

immediate and vast popularity of rock festivals posed a very specific

land-use problem. Places like Indian Reservations and farms were not

really viable for major, multi-day events, since too many things could

go wrong. Equally importantly, despite or because of the increasing

crowds, it was all but inevitable that rock festivals would become "free

concerts." Liberating as this may have seemed at the time, it ensured

that the events could not make enough money to provide a safe,

repeatable event for bands, patrons and host communities. The financial

opportunities of rock festivals were huge, however, and since nothing

says "rock and roll" like "land use," over the years there was a

concerted effort in the concert industry to find spaces that could

successfully and profitably host occasional, loud outdoor events with

giant crowds.

One of the intriguing solutions for hosting giant rock

festivals was to use facilities designed for auto racing. Race tracks

were usually somewhat removed from urban areas while still being near

enough to civilization to attract a crowd. Auto races themselves were

noisy, and major race events tended to occur just a few times a year and

last an entire weekend, just like a rock festival. Since race tracks

were permanent facilities, they generally had fences, bathrooms, water,

power and parking, so in many ways they would seem like ideal venues for

huge rock events. Indeed, some of the major rock events of the 1969 and

the 1970s were held at race tracks.

Two of the most successful

rock festivals were held at Dallas International Speedway and Atlanta International Raceway, both

organized in 1969 by promoter Alex Cooley. Both tracks were giant NASCAR

"super-speedway" ovals. The Rolling Stones' debacle at tiny Altamont Speedway might not

have happened had it been held at its original site,

the newly-opened Sonoma Raceway, then a newly opened Road Course in rural Sonoma County,

near the San Francisco Bay.

I looked at some of the history and economic dynamics of Auto Racing tracks as Rock Concert sites in another post, although for purposes of scale I focused on the Grateful Dead.

Generally speaking, while auto racing had been popular since the

invention of the automobile, horse racing had been hugely popular in

cities and county fairs throughout the United States, long before cars

were invented. However, after WW2, when the GIs returned and economy

boomed, America moved from its rural roots to a more urban and suburban

universe, and the automobile became a more important part of everyone's

life. A national boom in the popularity of auto racing corresponded with

a slow decline in the popularity of horse racing.

By the early

1960s, numerous custom-built facilities served the hugely popular auto

racing industry, with oval tracks (for NASCAR and "Indianapolis" cars in

the South and Midwest), road courses (for sports cars on both coasts)

and dragstrips (nationwide). These facilities were actually ready-made for rock

concerts, but there were some huge cultural divides. With a middle-class

family audience for auto races, and their Dow Industrial sponsorship

from major companies, racetrack promoters were neither tuned into nor

inclined to sponsor long-haired outlaw rock concert events flaunting

nudity and drugs.

|

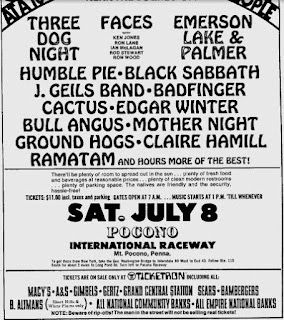

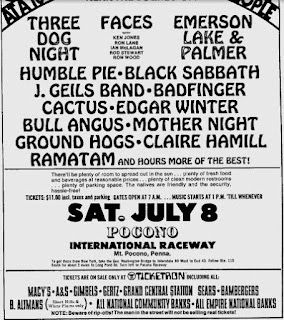

On July 8, 1972, Concert 10 presented a multi-act rock show at Pocono International Raceway in Long Pond, PA. Due to a huge rainstorm, the headliners did not appear until the dawn hours of July 9. The fine print says "the natives are friendly and the security, hassle-free"

|

Rock Concert Economics: 1973In 1973, there was a huge audience for

live rock music, but that audience was young, and without much ready

cash. Also, since rock music stood for "rebellion," the most popular of

rock music attractions were vulnerable to the complaint that they were

charging "too much" for tickets. The inevitable result of these

pressures was that popular rock bands put on concerts in larger and

larger venues, instead of charging more at smaller places. By 1973, the most popular bands were selling out

basketball arenas with capacities of 12,000 or more, even in so-called

"secondary" markets. Ticket prices were reasonable, around 4 or 5

dollars usually, but the total number of tickets sold was larger than

ever.

By the early 70s, multi-act "Festival" shows had mostly

been financial debacles and public relations disaster, and it wasn't

just Altamont: check out the saga of the "Erie Canal Soda Pop Festival"

in Griffin, Indiana on Labor Day weekend of 1972. Smart promoters were looking

for other workable venues, and race tracks re-appeared on the horizon.

An interesting thing to consider about auto racing was that--because of

the noise--they had to generally be well outside any populated areas,

but still within driving distance of a lot of potential fans. At the

same time, since fans had to drive a fair amount, a race track generally

offered a whole slew of races during a weekend at the track, not just a headline race.

These economics pretty much defined multi-act rock concerts, just for a

different, younger fan base.

On July 8, 1972 there had been a huge multi-act rock festival at Pocono Raceway in Pennsylvania. Pocono Speedway, in rural Long Pond, was nonetheless in driving distance for a huge population of teenagers in greater Pennsylvania and parts of Northern New Jersey. Pocono Raceway was less than an hour from

Scranton, Allentown and Nazareth, and about 90 minutes from the suburbs

of Philadelphia and Newark. There was a huge population of suburban rock

fans with access to their parent's cars. 120,000 fans showed up to see

Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Faces, Humble Pie, Three Dog Night and and

numerous other bands, completely overwhelming the facility. The interest

was there.

The parallel development at this time was rock concerts at football or baseball stadiums, full-size major league ones. There had been experiments with stadiums going back to the Beatles, but they had been unsatisfactory. The live rock music audience had gotten bigger, however, and sound systems had improved as well. The first "modern" rock concerts at football stadiums were on May 4 and 5, 1973, when Concerts West hsd produced Led Zeppelin shows at Tampa Stadium and also at Fulton County Stadium in Atlanta. Upwards of 40,000 fans attended each concert. All fans bought tickets, too, setting paid attendance records at the time for such venues. Uniquely, Led Zeppelin were the only act for both shows, with no opening bands.

The rock market was finding new mega-venues, and Bill Graham wasn't going to be left out. Graham was a self-promoter, yes, but he thought big--he was going to break in two mega-venues of his own, one at home in the Bay Area and the other down in Southern California.

Bill Graham was the king of concert production in San Francisco, but he had only occasionally put on shows in Los Angeles. Southern California did not have a dominant promoter, however, so there was still room for Bill to operate. To do that, however, he needed to make a splash, and to make a splash he needed a place. It looked like that place was the Ontario Motor Speedway, an innovative and newly constructed auto racing track that had only opened for full-time racing in Summer 1970.

The city of Ontario, CA, had been founded in 1891, and named by transplanted Canadians. Ontario is 35 miles East of Los Angeles, and 23 miles South of San Bernardino. Part of San Bernardino County, it is on the Western Edge of the proverbial Inland Empire. Ontario had been the site of a World War 2 Army Air Force Base, which remained an Air National Guard base after the war (and would remain so through 1995). The airport had also been established for civilian use in 1946 as Ontario International Airport. The Airport was joined to LAX in 1967, and jet flights had begun at the airport in 1968. Although Ontario only had a population of 64,118 in the 1970 census, as a result of the airport and the airbase it was at the nexus of a substantial freeway network. I-10 and I-15 met at Ontario Airport, so all of Southern California could get there easily.

Auto racing was booming in the 1960s, yet Los Angeles was underserved by facilities. Yes, there was the epic Riverside Raceway, another 25 miles East, but that made it even farther from LA proper. More importantly, Riverside was just a road racing facility--albeit a great one--and that limited the types of major events that could be held there. Ontario Motor Speedway was conceived as a full-service answer to every auto racing sector in the Los Angeles area, in a location near the city. The airport location was crucial, too, since major auto racing teams barnstormed around the country like touring rock bands, and drivers and even their race cars were often flying directly from track to track.

Ontario Motor Speedway was custom built to provide first class facilities for all the major types of racing: an oval for NASCAR and Indianapolis cars, a road course (that included part of the oval) for road racing and a dragstrip. Besides advanced pit facilities, OMS also pioneered what we now call "clubhouses" and "luxury suites" for sponsors. It was a well-conceived endeavor. The plan was to have not only top level NASCAR and USAC (Indy Car) 500-mile races, but Formula 1 and NHRA Drag racing. The inaugural race was the (Indy Car) California 500 on September 6, 1970, with paid attendance of 178,000, a huge crowd even by auto racing standards. Jim McElreath beat out an All-Star field of drivers that included Mario Andretti, A. J. Foyt, Dan Gurney and the Unser brothers.

|

Mario Andretti (5) in a Ferrari 312B F1 car, about to lap Mark Donohue (26) in a Lola-T192 Chevy F5000 car. Andretti would win the Questor Grand Prix, the only F1 race at Ontario Motor Speedway, on March 28, 1971

|

After a hugely successful opening, however, Ontario Motor Speedway had a number of events in 1971 and '72 that did not live up to financial expectations. The racing was great--it was the early 70s--but after the September '70 opening, the Speedway didn't catch LA like it should. The big plan was that Ontario would host a 2nd United States Grand Prix, which hitherto had been the exclusive province of Watkins Glen in New York.

As a prelude, Ontario Motor Speedway held a non-Championship Formula 1 race, the Questor Grand Prix, on March 28, 1971, won by Mario Andretti in a Ferrari 312B. The event was a financial bust, however, and Formula 1 cars never ran at Ontario again (ultimately

Long Beach, CA, would get the second US Grand Prix). Although 1971 went alright, the 1972 Ontario attendance, despite great racing, were a financial letdown. Thus by 1973, Ontario Motor Speedway would have been open to the possibility of different promotions.

|

Anaheim Stadium, Anaheim, CA July 10, 1973

|

Southern California StadiumsThere were plenty of stadiums in Southern California, but none of them were particularly ripe for rock concert promoters. Dodger Stadium was under the full control of the Dodgers, and they didn't share it. The Los Angeles Coliseum was old (opened 1921) and in and was near "undesirable" (read: "too African-American") neighborhoods. The Rose Bowl, in Pasadena, had access and parking issues. That left Anaheim Stadium, in Orange County. But it was just across the road from Disneyland, and The Mouse would not want weekend parking disrupted by hordes of young rock fans. In fact, starting around 1976, Anaheim Stadium would become the primary home of stadium rock concerts in Southern California, with the full cooperation of Disneyland, but that was a few years away. In any case, Bill Graham was from out-of-town, not well-placed to talk local stadium operators into cooperating.

Ontario Motor Speedway was a different matter. It had been well-conceived and well-built, but after initial excitement, the attention had died down--same as it ever was for LA--and it was going to need additional sources of revenue. May 27, 1973 was the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, and the biggest day for auto racing in America. Since all American race fans would be glued to their Televisions watching the 57th running of the Indianapolis 500, it was a perfect day for Ontario Motor Speedway to try something else. Bill Graham had figured out that he had a perfect venue in Southern California, and more importantly, a venue that needed him and his rock-concert expertise.

What did the Ontario Motor Speedway offer as a rock concert venue?

- Its location (35 miles E of LA, 23 miles Southwest of San Bernardino) put in close proximity to tens of thousands of potential rock fans.

- The convergence of the I-10 and I-15 freeways meant that an even larger pool of rock fans could drive to the Speedway fairly easily, from either San Diego (on I-15) or nearer the Pacific Coast (I-10). Ontario was just outside of Central LA, so the majority of potential fans could circumnavigate the often brutal traffic jams that the region was infamous for.

- In Southern California, it's always sunny and it never rains, so weather wasn't a consideration.

- The racing facility had parking for 50,000 cars, and apparently there were satellite lots as well. No need to worry about cars abandoned by the side of the road on some farm road.

- The grandstands featured 95,000 seats, with 40,000 "bleacher" seats in temporary grandstands, and a substantial crowd could fit on the infield. It was plausible to imagine 200,000 or more fans at an Ontario Speedway rock concert (178,000 had attended the inaugural California 500 race). This was double the capacity of even the enormous LA Coliseum.

- Ontario Motor Speedway had debt to service and was looking for other sources of revenue, so they would be eager to work with a partner like Bill Graham.

- Most importantly, the huge grandstands around the track, and hence around the facility, ensured that the facility was cordoned off. That meant it was plausible to ensure that only those with tickets would get into the show. At giant rock festivals, the economic issue was always gate-crashing, but that was usually in some giant, muddy field. The Speedway acted as fence, and entry was through controlled tunnels under the grandstands.

|

Robert Hilburn's column in the LA Times May 5, 1973

|

A feature in the Los Angeles Times mapped out the strategy I described above. Robert Hilburn was the Times' principal rock critic, and he had a "Saturday Roundup." On May 5, the Ontario Speedway concert was the primary topic, with a photo of Gregg Allman and quotes from a high-powered public relations executive (remember, in Los Angeles, PR equaled prestige).

Bill Graham Going All Out For Rock (Robert Hilburn, LA Times May 5 '73)

Bill Graham, rock's most creative--and often controversial--concert producer, is staging an all-day (8am to 5:30pm) rock show May 27 at the Ontario Speedway featuring the Grateful Dead, Allman Brothers Band and Waylon Jennings. Upwards of 150,000 persons are expected.

It's ironic, of course, that Graham, once so critical of outdoor festivals and other big-money events that lured rock stars away from more intimate ballrooms such as his Fillmores East and West, should be the man behind the Ontario spectacular, but there is no one better equipped to make the event a success. Graham, even his severest critics will conceded, puts together the best concerts in rock.

Though most of his energy is spent in San Francisco (he produces concerts regularly at Winterland and the Berkeley Community Theater), Graham does produce occasional shows in Los Angeles, most notably The Rolling Stones' benefit concert last January at the Inglewood Forum.

Gary Stromberg, a partner in the Gibson & Stromberg public relations firm, said special security measures will be taken for the concert. "California Highway Patrol, Sheriff's Department officers and local police will have road checks within five miles of the Speedway to insure that only cars with special stickers and concert tickets will be allowed in the vicinity."

Stromberg also said the Speedway has high fences and special tunnel entrances that were built specifically to deter would-be gate-crashers. There is parking at the Speedway, he added, for approximately 50,000 cars.

The event is titled "A Happening on the Green," and special non-musical treats are reportedly being arranged by Graham.

|

This aerial shot of Kezar Stadium (exact date uncertain)

|

Meanwhile, Back In San FranciscoWhatever your modern-day view of Bill Graham might be, he didn't think small. In May 1973, Graham was planning to expand his empire with a dramatic entrance into the Southern California market. But he had big plans for Northern California as well. On May 4, information was quietly leaked (through the Hayward

Daily Review rock column "KG") that the Grateful Dead would headline two concerts at the Cow Palace on Tuesday and Wednesday, May 21-22. Also on the bill would be Willie Nelson and the New Riders of The Purple Sage. This was a surprising booking on a number of levels.

The Grateful Dead had an extraordinarily loyal audience in San Francisco, but the band wasn't really that big. The Dead had headlined three weeknight concerts at the (officially) 5400-capacity Winterland back in December (Sunday-Tuesday December 10-12), followed by New Year's Eve. Those four shows had sold out without meaningful advertising. Yet the Cow Palace was a 16,000-capacity barn in Daly City, on the outskirts of San Francisco. Were there really enough Dead fans to fill it up for two weeknights? Willie Nelson was a rising star at this time, but he was no proven commodity in the Bay Area. Tickets went on sale, but it almost seemed to be a stealth show.

|

The San Francisco Examiner, May 14, 1973

|

On Monday, May 14, Graham showed his hand. The two Cow Palace Grateful Dead concerts were rescheduled for Saturday, May 26 at Kezar Stadium in Golden Gate Park. Kezar Stadium, opened in 1925, had been the home of the San Francisco 49ers until the 1971 NFL season. Kezar was now largely unused, but it was in the center of the city and relatively easy to get to by freeway from surrounding counties. On top of that, most Bay Area residents knew how to get to Golden Gate Park, so it was a workable destination. Kezar was small for an NFL stadium (about 60,000), but huge for a concert facility. With no competing sports dates, Kezar would be easier to schedule than an active stadium.

More importantly, the weekend after the Grateful Dead, Graham announced that Led Zeppelin was going to headline Kezar Stadium. As noted, Zeppelin had begun their tour by headlining stadiums in Tampa and Atlanta. Now Graham was going to book Zep's biggest concert on the West Coast. Over the course of just eight days, Graham was planning to put on the Grateful Dead at Kezar (Saturday May 26, with Waylon replacing Willie), the Allman Brothers and the Dead at Ontario (Sunday May 27) and Led Zeppelin back at Kezar (Saturday June 2).

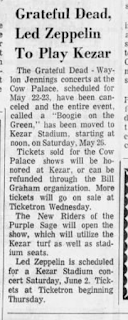

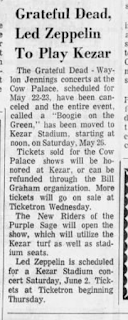

Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin To Play Kezar (SF Examiner, May 14 '73)

The Grateful Dead-Waylon Jennings concerts scheduled for May 22-23, have been canceled and the entire event, called a "Boogie on the Green," has been moved to Kezar Stadium, starting at noon, on Saturday, May 26.

Tickets sold for the Cow Palace shows will be honored at Kezar, or can be refunded through the Bill Graham organization. More tickets will go on sale at Ticketron Wednesday.

The New Riders of the Purple Sage will open the show, which will utilize the Kezar turf as well as stadium seats.

Led Zeppelin is scheduled for a Kezar Stadium concert Saturday, June 2. Tickets at Ticketron beginning Thursday.

The Grateful Dead/Waylon Jennings show at Kezar drew about 30,000 fans, and was a huge success. The Led Zeppelin show on the next weekend was sold out, drawing twice as many fans. The noise bothered the local neighborhood--the sound system was in a different location than it had been for the Dead--, and Led Zeppelin's fans were not as welcome in the Haight-Ashbury as Deadheads. Bill Graham had proof-of-concept for his "Day On The Green" all-day stadium concerts, but he moved them to the more accessible Oakland Coliseum. They would thrive there for many decades.

|

May 12, 1973 Pomona Progress-Bulletin listing

|

May 1973 Status Report: Allman Brothers, Grateful Dead, Waylon Jennings, New Riders

The Allman Brothers Band would be the premier attraction at the Watkins Glen Summer Jam concert on July 28, 1973, attracting around 600,000 fans. 150,000 of them even paid. From the Summer of 1973 through the Fall of 1975 the Allman Brothers were one of the premier concert attractions in the country. You can make a good case that Led Zeppelin and Emerson, Lake & Palmer were equally as popular as the Allmans, but they weren't bigger. Now, granted, the Rolling Stones didn't tour and Bob Dylan only played indoor arenas, but the Allmans were a massive outdoor draw all over the country. Watkins Glen was the biggest, by far, but it wasn't a fluke.

Most rock fans from the era recall that Summer '73 was when the Allmans broke through with their mega-hit "Ramblin' Man," a catchy country tune that was not particularly typical of the bluesy jamming on which the Brothers had made their bones. "Ramblin' Man" was reminiscent of "Blue Sky," sure, and maybe "Revival," both of them Dickey Betts songs as well, but it wasn't at all like "Statesboro Blues" or "Whipping Post." So the idea that the Allmans began to dominate the US concert market when they got their big hit single is compelling. But it's wrong.

The Allman Brothers had a massive successful US tour in the Summer of 1973. The first highlight was an epic double-bill with the Grateful Dead at Washington, DC's RFK Stadium, on the weekend of June 9-10. Yet that event was eclipsed by the triple-bill at Watkins Glen on July 28. Nonetheless, the Allmans' follow-up release to Eat A Peach, which had come out back in February '72, would not even be released until August of '73, after the Watkins Glen show. "Ramblin' Man" was the first single, released at the same time, and it would go on to reach #2 on the Billboard charts. Now, sure, advance copies of Brothers And Sisters and the "Ramblin' Man" 45 were probably on FM radio (or even AM) in late July, but the huge successes of RFK and Watkins Glen were before the album and single had even been released. The Allman Brothers Band were huge because they were huge. FM radio listeners had caught up to them, and FM radio played them constantly throughout 1972 and '73.

The Allman Brothers Band's third album At Fillmore East had been released in July 1971. As America was slowly catching up to their stunning sound, Duane Allman was killed in a motorcycle accident on October 29, 1971. As a result, the band's followup, Eat A Peach, a double-lp that was half studio and half live, received extraordinary (if well-deserved) attention. And if that wasn't enough, Derek And The Dominos had a hit in Summer '72 with the by-now18 month-old "Layla," and Duane's interplay with Eric Clapton drew even more attention to him. The Allmans were in the process of recording the sequel when bassist Berry Oakley died in a motorcycle accident almost exactly a year after Duane (on November 11, 1972). Interest in the Allmans inevitably redoubled. In 1973, Capricorn Records released a double album of their first two records (Allman Brothers Band and Idlewild South) as Beginnings, so the Allmans were all over the radio throughout the Summer, even though they did not yet have a new album.

The Grateful Dead, meanwhile, had risen above the level of cult status, even if they were only somewhat of a "major attraction." The band had released four gold albums in a row (Workingman's Dead, American Beauty, Grateful Dead ['Skull & Roses'] and Europe '72), and they, too, got their share of play on FM radio. In the case of the Dead, the songs played on FM were likely the more rocking songs in their repertoire (like "Bertha" or "Sugar Magnolia"), rather than big jams like "Dark Star," but they were Dead songs nonetheless. The Dead would leave Warner Brothers to go independent at the end of 72, but they would not release their final record on the label (Bear's Choice) until July of '73.

The New Riders of The Purple Sage no longer featured any members of the Grateful Dead, but they still shared booking and other services with them. By May 1973, the Riders had released three albums on Columbia. The Dead tried to book the Riders as openers when it fit. Clearly, they fit in at Kezar but not Ontario.

Waylon Jennings (1937-2002) was an established country singer, but

he had roots in rock and roll. Jennings had been the bass player for

Buddy Holly and The Crickets, and had graciously offered to give up his

seat on the airplane to The Big Bopper, on the fateful flight on

February 3, 1959 that crashed, killing Holly, the Bopper, and Ritchie

Valens. Jennings had gone on to success as a Nashville singer, but he

had never been happy with how his records were made. By '73, country rock was starting to become a commercially viable enterprise, with the Eagles as the most prominent band, along with a slew of other groups like Poco, the New Riders and Pure Prarie League. The unhappy Jennings, however, tapped into something much more potent than hippies playing rock and roll with a twang.

The more potent and lasting merger of country music and the 60s would be the music coming out of Austin, TX. Genuine country musicians, with proper Nashville pedigrees, would move to Austin, grow their hair, light one up and pretty much play the same music they had been playing before. OK--maybe there was a bit more attitude, but that wasn't incompatible with older roughneck country, anyway. One of the earliest converts was Jennings.

In 1972, Jennings had had a pretty good hit with the song "Ladies Love Outlaws," and RCA still wanted him to be a typical Nashville artist. By 1973, however, Jennings had moved to Austin, TX, to join fellow outcast Willie Nelson, and RCA finally saw the light. Jennings kept the beard he had grown, and "Outlaw Country" followed, with Willie and Waylon in the forefront. Sharing bills with the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers in California was a huge break from country practice. Jennings was consciously and enthusiastically aligning his music with long hair, weed and loud, loud music.

What Happened: Ontario Motor SpeedwayOn Monday, May 22, Robert Hilburn explained in the Los Angeles

Times that the Dead/Allmans/Waylon concert would be canceled. The reason given was that the police were going to insist that the concert end by nightfall, because of some incident at a concert in Stockton.

Ontario Rock Concert Canceled by Graham (Hilburn LA Times May 22 '73)

The all-day Grateful Dead-Allman Brothers-Waylon Jennings rock concert Sunday at the Ontario Motor Speedway--which had been expected to draw upwards of 150,000 persons--has been canceled, producer Bill Graham has announced.

"Trouble with several youngsters at an April 29 outdoor concert in Stockton caused Ontario civic official to take a hard, long look at the May date," Graham, who was not involved in the Stockton event, said. Specifically, police said the concert--the first of its kind at the huge speedway--would have to end three hours before dark, or approximately 5:54pm, he added.

Since the Allmans and the Grateful Dead were scheduled to play several hours each, Graham said he doubted he could honestly end the show by that time." He pointed out the Dead played six hours recently at an outdoor concert in Des Moines, Iowa. Though normally outspoken, Graham made it clear he was not blaming anyone. "All the Ontario officials and police were extremely cooperative. Under the time limits imposed however, I didn't feel we could have given the kids the show we promised.

Graham said he is proceeding with plans to present Leon Russell Aug. 5 at the Ontario facility. Ticket sales for the Sunday event were described as "healthy" by a spokesman for the San Francisco-based producer.

You can buy this story if you like. Maybe there were some elements of truth to it, I don't know. Here's what I think--the concert didn't sell enough advance tickets, and it no longer made economic sense. Remember, Graham's team would have had to construct a huge stage and a ginormous sound system, and fly the Allman Brothers, the Dead and Waylon Jennings in from out of town. The Times article says that the concert was "expected to draw upwards of 150,000 patrons." If Graham had those kind of ticket sales, he would have found a way around any police objections (if those objections were real), by paying for better lighting, more security or whatever it took. But I don't think the ticket sales were there. Given that we know that the Allmans and the Dead would pack Watkins Glen just two months later, why could that have been?

|

Although this fine album was a massive hit, it doesn't shout "Los Angeles Summer of '73" to me

|

The West and The EastThe West Coast and the the East Coast were very different concert markets in the 1970s. The Midwest and the South probably were different, too, but I have done less research into them, so I won't generalize. A characteristic of East Coast events from 1969 onwards was the willingness of large numbers of young people to get in their cars and travel for rock concerts. An event like Woodstock drew not just from New York state but all of New England, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Population was much more distributed in the East. There were a lot of medium-sized cities full of young people anxious to see major rock bands, and they would travel. The phenomenon of Deadheads driving hundreds of miles to every show originated as an East Coast phenomenon.

The West, even in California, was considerably less populated in the 1970s. The vast suburbs of Los Angeles, the Bay Area, Fresno and Vegas were far smaller then. It wasn't that young people didn't love rock and roll as much, they surely did, but once you got outside the major metro suburbs, there just weren't that many people. Fresno, to name just one outlying city, had 165,655 residents in the 1970 census, while it would have 542,107 in 2020. There were just fewer young people ready to hop in their parents' cars and see a big rock show. Few Deadheads from San Francisco would have been planning to travel down to Ontario, since the Dead were playing the afternoon before. As for LA, the Dead had already booked three shows at the Universal Amphitheatre on June 29-July 1, so it's not like Deadheads would lose out.

|

Los Angeles and San Francisco aren't the same, which is what makes California great

|

Also, while both the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers were popular bands, I don't think they were particularly popular in 1973 Los Angeles. Now, sure, there were plenty of fans who liked each band, or both bands. But LA was huge, so any band could sell tickets--Jethro Tull, Black Oak Arkansas, The Yes, you name it. But the Allmans and the Dead were hippie guitar hero bands--was that what was happening and what was going to impress everybody in LA on Monday morning when you got back to school? I don't think so.

Did the Allmans or the Dead have a hit single on the radio? Definitely not. Did this matter in Los Angeles? Well, you decide, but it was the biggest record industry town in the history of the record industry, so I think you had to be super-cool or on the charts, and the Dead and the Allmans were neither. I think ticket sales were tepid, and Graham canceled the show.

Some months later, in the East it was different. The tens of thousands who bought tickets for Watkins Glen weren't downtown Greenwich Village hipsters, they were kids in Syracuse or Allentown or Parsippany who wanted to see some big time rock bands. None of those bands were coming to their town, and their parents weren't necessarily OK with them driving to Manhattan, but some racetrack out in the countryside? Yeah, why not? The kids could have got permission to go the US Grand Prix, so why not a concert?

Graham's assessment of the Allman Brothers and the Dead as a booking pair was correct, but his location was off by 3000 miles. He was also right about the Ontario Motor Speedway, although he picked the wrong bands. The following Spring, Ontario Motor Speedway would hold the "California Jam" on April 6, 1974, an all-day affair headlined by Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Deep Purple and the Eagles. Actual attendance was well North of 200,000, but more importantly paid attendance was around 168,000, breaking every record known for a paying concert. That record would hold until "Cal Jam 2," also at Ontario Motor Speedway, on March 18, 1978. Cal Jam 2 had at least 175,000 paid.

So the planned May 27, 1973 concert at Ontario Motor Speedway had all the right pieces for an epic success of unimagined proportions, but in the wrong combination. We are left with only a poster.