|

| The two May '73 Garcia/Saunders shows at Homer's Warehouse were broadcast on KZSU-fm |

Jerry Garcia had a long and storied history as a performing artist, in numerous aggregations, the most famous of which was the Grateful Dead. One of the many innovations that the Dead popularized for rock music were live performance broadcasts. A few legendary radio stations, like KSAN-fm in San Francisco, KPFA-fm in Berkeley and WNEW-fm in New York, have a particularly legendary status amongst Deadheads for their historic and widely circulated broadcasts of Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia concerts. Yet the first, seminal and arguably longest broadcaster of Garcia performances has gone largely unnoticed. KZSU, the Stanford University radio station, not only broadcast Jerry Garcia as far back as late 1962, they broadcast him regularly until 1988. The only comparable station in Garcia or Dead history might be KPFA-fm in Berkeley, which has an equally storied Jerriad saga, which I will get to eventually. I wrote an extensive post on Jerry Garcia's performance history on KZSU in the early 60s.

Appropriately enough, Jerry Garcia's first studio recording was broadcast on KZSU in Fall 1962, and the Garcia Estate has released that long lost recording as Folk Time. The story of KZSU and Jerry Garcia, however, went far beyond the early 1960s, so in this post I will unravel the tale of Garcia's 70s and 80s performances on KZSU.

KZSU-880 AM and 90.1 FM

Stanford University radio station KZSU had been founded in 1947. Initially it was only accessible on 880-AM on the Stanford campus dorms and fraternities. Throughout the 1960s, however, almost all Stanford undergraduates lived on campus. Undergraduate women were required to live in campus in the dorms, as sororities had been closed some decades earlier. Thus, while KZSU had limited range, it had an outsized importance to campus life. In 1964, KZSU added an FM frequency. 90.1 FM was accessible to all, but since the transmitter had only 10 Watts, KZSU-fm was only audible in Palo Alto and Menlo Park. In the 1960s, however, FM receivers were rare, and usually confined to the type of guy--always a guy--with an expensive "Hi-Fi" stereo receiver (for more detail about KZSU, see Appendix 1 below).

Two restless young doctors had started a Folk Club above The Tangent deli at 117 University Avenue in Palo Alto. It was near the campus, and serious folk music was usually directed at college students. Stanford student Ted Claire arranged to tape the weekend shows at the Top Of The Tangent for a weekly Tuesday night broadcast on KZSU called "Flint Hill Special." Although only audible in the dorms (and frats), the Flint Hill Special is why there were tapes of Jerry Garcia in various ensembles in 1963 and 1964 (some later released as Before The Dead). KZSU broadcast live tapes of folk music from the Top Of The Tangent at least as late as the Summer of 1964 (for a summary of the early days of live broadcasts on KZSU, see the summary in Appendix 2, and see my earlier post for more detail).

|

| The July 4, 1967 Stanford Daily described the Grateful Dead's appearance at a Be-In at Palo Alto's El Camino Park on Sunday, July 2 |

Live Rock Music In Downtown Palo Alto

Folk music was popular at Stanford and in Palo Alto, but it disappeared in a cloud of funny smelling smoke. This happened in college towns and Universities all over the United States, particularly on the West Coast and the Northeast. In Palo Alto, however, unlike every other place, these strange influences weren't some mystery wind blowing in from out of town. The call, as they say, was coming from inside the house. The Top of The Tangent crowd were right in the thick of the psychedelic revolution. Ground Zero was Ken Kesey's cottage on Perry Lane in Menlo Park, within easy walking distance of the Tangent. The doors of perception were busted open a few miles South of the Tangent--but still in Palo Alto--at the Palo Alto Acid Test at The Big Beat on December 18, 1965.

In 1966, Stanford University held numerous rock concerts, featuring legendary acts in their prime. Yet the Grateful Dead had played the Tresidder Student Union on October 14, 1966 and there were no more concerts in Stanford facilities. Big Brother and The Holding Company headlined a "Happening" at the Wilbur dorm complex on December 3, 1966, and no such events were ever held again, at least officially. Good times were being had, very good times, and Stanford University was definitely not down with it.

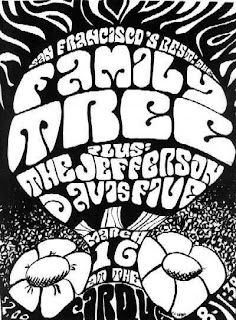

Two things happened in downtown Palo Alto in the Spring and Summer of 1967, within a few blocks of each other. First, in April of 1967, a fish-n-chips joint at 135 University (at High Street), just two doors from the Tangent, added live bands and a light show. In 1967, Fish-and-Chips was exotic foreign cuisine (I swear I am not making this up--the competing shop was called H Salt), so that made the Poppycock suitably exotic for must-be-cool Palo Alto. Also, there were no bars in downtown Palo Alto (nor would there be until 1981), so a place that served foreign food and beer to hippies was enough for a hip music hangout.

The second thing was that some rebellious University types started something called The MidPeninsula Free University, known locally as "Free You." Free You offered non-standard classes. All jokes about "underwater basket-weaving" for college credit can be traced back to Free You. To raise money, the MPFU had a series of free "Be-In" concerts at El Camino Park, just a few blocks from the Tangent and the Poppycock. How free concerts raised money has never been fully explained, but Palo Alto had six such events in 1967 and '68. The most famous one was July 2, 1967, when the Grateful Dead returned to town to headline the Mary Poppins Umbrella Festival on a Sunday afternoon. The musicians from the Tangent had returned, heavily armed with electricity.

Over at the Poppycock, the house band was The Flowers, who had changed their name to Solid State by the time of the Mary Poppins Umbrella Fest. The Flowers were mostly a jazz group, but they played electric instruments, loud, and they had the old equipment from the Merry Pranksters, so they were part of the new psychedelic rock world (you can read the entire saga of The Flowers in a different post). Initially, the Flowers, and later Solid State, played every weekend at the Poppycock, but over time the club booked different acts every weekend. It was the Bay Area in the late 60s--there were plenty of bands, and a lot of them were really good.

|

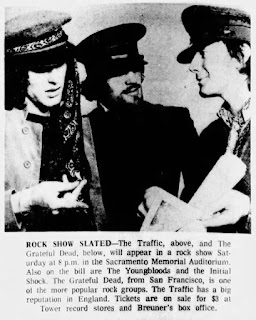

| The Stanford Daily of April 19, 1968 mentions broadcasting then-unknown Creedence Clearwater Revival live (on KZSU-fm radio) |

KZSU-fm Live Broadcasts

It's always fun to make fun of Palo Alto--I never tire of it--but the city has legs to stand on. There were lots of college radio stations in the 1960s, most of them fairly dormant until the 1970s. KZSU, however, started doing live remote broadcasts from the Poppycock as early as February 1968. At this time, KMPX-fm in San Francisco was quite literally the first "underground" rock radio station in the country, and they had only started doing live rock broadcasts in the Summer of '67. KZSU very well may have been the second such station. The initial broadcast (per the Stanford Daily) was a comedy trio called Congress Of Wonders. Congress Of Wonders is largely forgotten now, but their hip comedy was played regularly on the radio once their albums were released ("Pigeon Park" remains a classic).

The first real rock band broadcast from the Poppycock by KZSU was on March 22, 1968, featuring another local act: the newly-named Creedence Clearwater Revival. The band headlined the Poppycock on Friday and Saturday night, and the first set on Friday night was broadcast on the radio station. It would only be audible on the Stanford campus and nearby Palo Alto and Menlo Park, but who else was going to the Poppycock? No tape survives of this, to my knowledge, but the fact that it happened at all sets Palo Alto apart whether you like it or not.

As to other events, a tape has circulated of the Lafayette (Contra Costa County) band Frumious Bandersnatch, from May 31, 1969. The Stanford Daily mentioned a few broadcasts as well: The Apple Valley Playboys on November 26, 1969, and the bluegrass team of Vern And Ray on January 22, 1970. I suspect there were a few other live broadcasts from The Poppycock in '68 and '69 that for which we have no references. The Poppycock closed in Spring 1970, squeezed because its small size (capacity probably about 250) was not substantial enough to book popular local bands. I know that Miles Davis was broadcast on KZSU when they broadcast his Frost Amphitheatre show on October 1, 1972, but I have no idea if jazz broadcasts were rare or common.In May, 1971, the site of The Poppycock became the club In Your Ear, which was sort of a jazz club, but with a much more eclectic booking policy. Besides jazz, In Your Ear featured blues, a little rock and some folk music, too, similar in many ways to what the Great American Music Hall would book a few years later. The intriguing club came to an abrupt halt when a pizza oven fire burned down the building on December 31, 1972. Live music pretty much disappeared from downtown Palo Alto after that.

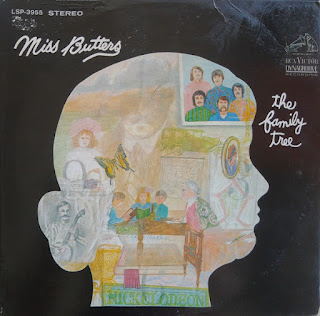

Homer's Warehouse, 79 Homer Avenue, Palo Alto, CA

Homer's Warehouse was an old quonset storage building next to the train tracks, at 79 Homer Avenue. It was in walking distance of downtown, although you had to take a pedestrian tunnel under the train tracks (for Palo Alto locals, Homer's Warehouse was behind Town And Country Village, and the site is now a parking lot for the Palo Alto Medical Center). The club was intermittently open in mid-1971, appealing to bikers and the like, and marginally tolerated by the police since it was not in downtown itself. In late 1972, the venue was taken over by local entrepreneurs Andrew Bernstein and Rollie Grogan. Bernstein wrote about his adventures at Homer's Warehouse in his 2018 self-published biography California Slim: The Music, The Magic and The Madness.

It is well-known that Jerry Garcia and Old And In The Way broadcast a set on KZSU on July 24, 1973. I myself heard that show. It was, quite literally, the first time I had ever heard bluegrass music. At the time, it was easier to read about new music than hear it. I had read that Garcia was playing banjo in a bluegrass group that played local clubs, but I was too young to go to any nightclub, and in any case I had no car and no money and lived in the suburbs. I knew that bluegrass was some sort of country sub-genre, but I didn't know what it sounded like. When I stumbled onto the KZSU broadcast that night--I used to listen to KZSU regularly--I knew it was Garcia playing bluegrass. It was the first time I heard "Panama Red" and "Lonesome LA Cowboy," among other things, as the New Riders of The Purple Sage versions had not yet been released. Andrew Bernstein describes booking Old And In The Way in some detail, including having Asleep At The Wheel as an opening act.

Bernstein was a Palo Alto native, and had taken banjo lessons from Garcia back in 1963 or so, as a high school student. He knew Kreutzmann and Pigpen as well, and while he hadn't been in touch with the Dead once they moved to San Francisco, he had more of a connection than a regular club owner might. Old And In The Way had been booked at Homer's Warehouse for one of their very first concerts back on March 8, 1973, and Garcia and Merl Saunders had played a successful weekend in May, and then Old and In The Way again later in May, so it's no surprise that Old And In The Way returned. The first set was broadcast, and people were implicitly encouraged to come down to the club for the second set. I could have walked the dog over there, I guess--it was only a few blocks away from my house--but I didn't realize that while I was listening.

Homer's Warehouse and KZSU

Bernstein tells an unheard story about the link between Homer's Warehouse and KZSU, and how they came to broadcast Jerry Garcia. Most intriguingly, Bernstein says that the two Garcia/Saunders shows at Homer's on May 4-5, 1973 were both broadcast on KZSU. Per Bernstein, the Old And In The Way July broadcast followed from the initial ones in May. We don't have any airchecks of the May JGMS shows, which isn't surprising, as few people had cassette decks, and fewer still would have been in the range of KZSU's 10-watt transmitters. In any case, we have Betty Boards for both shows, so we don't need the FM broadcasts. But Bernstein's descriptions of the circumstances of the KZSU broadcasts have gone unnoticed, so I am inserting them here (please note that 30 years after the fact, Bernstein's memories are not particularly sequential and some details appear questionable. Decide for yourself how much corrective analysis is needed). Bernstein describes the May 4 set-up in detail:

Rollie's [Grogan, Bernstein's partner] biggest triumph to date came on the afternoon he booked Jerry Garcia and Merl Saunders for a weekend show. Joining them on May 4th and 5th, 1973 would be John Kahn on electric bass and Ron Tutt, Elvis's old drummer and famed Nashville studio percussionist...[note: Tutt would not join the band until 1974, and Bill Vitt was likely the drummer]

There was yet another surprise waiting in the wings. Lobster [Paul Wells], one of our regulars, was part of the FM radio scene in the Bay Area at the time. He was big, loud and both a DJ at KSJO in San Jose and the musical director of KZSU, the Stanford radio station. One afternoon, he approached Rollie and me about broadcasting the Merl and Jerry shows live from Homer's on KZSU. Rollie and I both thought it was a great idea, so Lobster connected us with Mike Lopez, the student manager of the station. Lobster had told us that we would reach the whole Northern California market [note: this was completely untrue], but Mike had even bigger plans than that. It seems that Stanford had access to a transatlantic phone cable that had been dormant for many years, so Mike decided that what several Iron Curtain countries needed was a heavy dose of Jerry--via pirate radio from Homer's!

Mike's plan called for Hungary, Belarus and parts of East Germany to receive the feed. However, first we needed to get permission from Jerry, which meant going through Sam Cutler (more blow, please!). When Sam gave us the green light, it was full speed ahead. Of course, the university would know nothing of this little international broadcasting caper....

Around 10:00am on the day of the show, our Purple Room started to take on the look of a command center, overrun by cables and wires with crazy-looking guys from Stanford hooking up 20,000 watts [the Warehouse sound system]. Both shows would be taped on a gigantic Memorex reel-to-reel. It was a fuck-all, balls-to-the-wall extravaganza...

Around 3:00pm, the sound truck arrived with the road crew, and out stepped the lead technician for the night--Owsley Stanley.

Because of his eccentric and unpredictable character, Owsley didn't know how to finish a project on time, so he was banned from any involvement with sound when the Dead were on tour. However, for Jerry shows, he was "the man." His first task, when he got to Homer's, was to make sure the broadcasting guys from Stanford knew who was running the show. General Patton had arrived. Sound mix, PA levels, acoustics, tape speed, the whole shebang was under his direct control. The packed Purple Room was known that night as The Command Center.

Sam Cutler showed up around 5:00...by this time Owsley was like an obsessed woodpecker. He was a pain in the ass, but a perfectionist, eventually, with only fifteen minutes before the doors were scheduled to open for the Friday night show, we got the sound up and working to his desired metrics.

The music for the show started at 7:30pm sharp. Lobster was the live DJ, operating the radio control board for the broadcast out of the Purple Room. He was hyped, as we all were. I did the stage intros.

This is history in the making, I thought as I introduced the band.

Then I ran out to Rollie's car and turned on the radio...There we were coming through loud and clear. I tried to imagine some Hungarian family puzzled by what the hell they were listening to. I hope they enjoyed it.

According to Bernstein, not only was there a broadcast on May 4, the entire process was repeated the next night:

Once Owsley, Sam Cutler and their wild-eyed sound crew arrived, the madness set in once again. Unlike the day before, however, all the gear was already in place, so all they had to was push some buttons and turn some knobs

So Garcia apparently broadcast from KZSU three times in 1973, even though we only have the tape for the July Old And In The Way show.

Jerry Garcia and KZSU: Encore

Keystone Berkeley owner Freddie Herrera had opened a sister club in Palo Alto in early 1977. The Keystone in Palo Alto was at 260 South California Avenue, in a commercial district that was distinct from downtown and University Avenue. The commercial district (formerly the downtown of the town of Mayfield, which had merged with Palo Alto in 1925) was adjacent to the Stanford Campus, but not particularly near any student housing. In late 1977, the Keystone in Palo Alto started having regular Monday night broadcasts with the local "alternative" country station KFAT, in nearby Gilroy. The Monday "Fat Fry" broadcast the first set at the Keystone, to publicize the band and the club, and to encourage listeners to drop by for the second set. The second Fat Fry, in fact, on December 5, 1977, featured Robert Hunter and Comfort, with Bob Matthews and Betty Cantor mixing the sound for the radio. A similar effort was tried on one occasion with KZSU with Garcia.

On December 23, 1977, KZSU broadcast the first set of the Jerry Garcia Band from Keystone Palo Alto. Per an eyewitness, the dj started up the second set and then cut it off. I believe they didn't realize the concept was just to broadcast the opening set, to encourage late arrivals. While the KFAT Fat Fry continued to be broadcast from Keystone Palo Alto every Monday night for several more years, I'm not aware of other KZSU experiments. Of course, since KZSU was not a commercial station, their imperatives would have been different than KFAT's. In any case, we got a good tape of the first set from December 1977, at a time when quality JGB was not in circulation. How appropriate that Garcia was returning to where he had first broadcast, although I'm sure he was unaware of it at the time.

Final Homage

The Grateful Dead had an appropriately rocky history with Stanford University. The Dead's concert at Tressider Union on October 14, 1966 was the last concert there--good times I'll bet--and the Dead did not return until February 9, 1973 (when they played the Maples Pavilion basketball arena). When the Beta Theta Pi fraternity arranged to book Robert Hunter and Roadhog in May 1976, they were told the Grateful Dead were banned from campus. Of course, Bob Weir had played Frost Amphitheatre by that time, but there was at least some voodoo associated with the Grateful Dead name.

Nonetheless the Grateful Dead finally headlined Frost Amphitheatre in 1982, and played several weekends at the venue through 1989. By the time the Dead stopped playing there, the band was much too popular to play the 10,000-capacity bowl, and huge crowds congregated outside the venue. Stanford did not like the atmosphere, and unlike a commercial establishment, they did not really need the revenue. For the 1988 shows, however (Saturday and Sunday April 30 and May 1), I know that the shows were broadcast on KZSU to allow the huge parking lot crowd to hear them. [update 20231226: Commenter and former KZSU staffer reports that:

My KZSU friends have confirmed that we did broadcast the Grateful Dead Frost shows from 1985 to 1988 at least, with interviews of Healy in 1985, Mickey in 1986, and Jerry & Bobby in 1987 or 1988.

I'm not sure if this was done again on May 6 and 7,1989. After that there were no more Grateful Dead or Jerry Garcia concerts at Frost, anyway.

Update 20240109: Correspondent Geoff Reeves weighs in with the 411. All the Dead shows from 1985-89 were broadcast on KZSU, and there were numerous interviews too:

My name is Geoff Reeves and I was a staffer at KZSU for much of the 1980s. I kicked off the live broadcasts of the Dead at Frost in 1985 by calling up Dan Healey and convincing him we weren’t looking to score free tickets and were legitimately from KZSU. Dan helped get permission to broadcast live and figure out how to connect us to the board. A 5-year tradition began. And, yes I can confirm we broadcast live from 1985 through 1989. I’ve got board tapes of all 10 shows (with custom art on the labels :-) In addition to any broadcast recordings, we also made copies of the boards available to anyone wanting them so they should be in pretty wide circulation.

Around that time Dan started mixing ambient audience sounds into the board so the board tapes and broadcast had a much better live feel than the more ‘sterile’ boards from earlier times. More like audience tapes but mixed intentionally.

In 1986, we started recording interviews before the shows and during breaks to be broadcast after the live show ended. The ‘interviews’ with random deadheads were some of the most entertaining (when edited down) but over the years we interviewed Dan Healey, Dennis McNally, Wavy Gravy, Bill Graham, Mickey Heart, and, (eventually) Mickey, Jerry, & Bobby.

It may also be of interest to know that KZSU broadcast a program called Dead to the World during those years. The name poked fun at our still weak transmitters (100 W) but, hey, they could hear us as far away as Berkeley (sometimes).

Live Jerry Garcia music was first broadcast from the May 3, 1963 show at the Top Of The Tangent (probably broadcast on Tuesday, May 7). It was last broadcast on May 1, 1988, (or maybe May 7, 1989 from the Frost Amphitheatre, about a mile away. In between, Garcia was broadcast a surprising number of times, with a variety of ensembles, covering the arc of his career from struggling folk musician to rock guitar legend.

Appendix I: The Roots Of College Radio

One byproduct of the massive expansion of American higher education after World War 2 was the rise of radio stations associated with colleges and universities. In the Post WW2 universe, college was seen as more than just a degree factory where future employees were produced, and schools had a host of activities that were meant to broaden both the college community and the individual students themselves. In the case of Stanford University, radio station KZSU started in 1947 as part of the Department of Communication. KZSU facilities were used by the speech and drama department, although unlike some smaller schools, Stanford was not providing a professional program for future broadcasters. KZSU was only broadcast on 880 on the AM dial, and the station could only be heard in campus buildings, like dorms and fraternities.

By the early 1960s, radio played a more important part in student life, but KZSU was still a campus-only station. As far as I know, all Stanford freshmen and all women were required to live on campus. There was not enough housing for all undergraduates, so some Stanford men lived off campus, but I do know that the majority of undergraduate students still lived on campus in any case. All women students and all Freshman males lived in campus dorms. Some men also lived in fraternities, but the sororities had been shut down some decades earlier. KZSU broadcast to the dorms and fraternities.

Although KZSU was only audible on campus, it had an outsized importance to Stanford students. FM radio was exotic, and little was broadcast on it, and regular AM stations in San Francisco and San Jose were the only other options. There were a few Top 40 stations (KYA-1260 and KFRC-610 in the City, and KLIV-1590 in San Jose), a country station (KEEN-1370) and various news-talk-music stations for adults (like KSFO-560, KNBR-680, KCBS-740 and KGO-810). So Stanford's student-run-for-student-listeners station was a good choice for a dorm resident.

KZSU producers, announcers and disc jockeys were all students, or at least University-affiliated. The programs were a mixture of Stanford sports, news updates, documentary-type specials and lots of music. A wide spectrum of music was covered, including jazz and classical. It being the early 60s, when folk music was popular with college students, there was folk music on KZSU as well. Certainly more folk was broadcast on KZSU than was heard on any commercial station, and that is how the connection to The Top Of The Tangent came about.

Appendix II: "The Flint Hill Special" and The Top Of The Tangent

It is a well-known piece of Garciaography that Garcia and his folk pals really made their bones at a tiny folk club called The Top Of The Tangent in Palo Alto. What has remained under the radar is how critical KZSU was to the modest success of The Tangent. Without KZSU, the Top Of The Tangent might not have thrived, and thus the whole story of Garcia, Weir, Pigpen and Mother McRee's Uptown Jug Band Champions would have taken some different, unknown course.

I have discussed the history of The Top Of The Tangent at some length elsewhere, so I will only briefly recap it. Two restless young doctors, Dave Schoenstadt and Stu Goldstein, decided to start a folk club in eary 1963. Their only guide was a Pete Seeger book called How To Make A Hootenanny. There was a delicatessen at the end of University Avenue that was nearest Stanford, with an extra room above it. The two doctors arranged to have shows there on Friday and Saturday nights, as well as a "hoot night" on Wednesdays. The little room held about 75 people. Sometimes there were touring folk acts, but more often the performers were from the Bay Area folk scene. Locals who shined at hoot night got a chance to play on the weekends, and could build their own followings. The Tangent deli was at 117 University, and the folk club was above it--hence "The Top Of The Tangent." In reality, however, everyone just called the folk club "The Tangent," so I will do that hereafter.

Here's the reason we have those early Garcia tapes--throughout much of

1963, every weekend Tangent show was taped, and parts of all those shows

were broadcast on KZSU. I'll repeat that, just so you don't think I

mis-typed--almost every Tangent show through at least June 1963 was

taped, and parts of most of them were broadcast. So there's no mystery

why we have prehistoric Garcia tapes. Don't forget, by the way, that

everyone else who played the Tangent in '63--Pigpen, Peter Albin, Jorma

Kaukonen, Janis Joplin, Herb Petersen and many others--would have been

broadcast on KZSU as well. And yes, before we go on any further, I

assure you that the Garciaological equivalent of SEAL Team 6 has been on

the case for some time. If there's anything new to uncover, they'll get

it.

The two good doctors who ran the Top Of The Tangent knew that Stanford

students would be a key component of the audience of any folk club.

Since KZSU featured weekly shows of many different types of music, The

Tangent sponsored the Tuesday night folk show. The host was either

(Stanford student) Ted Claire or (Dr. and Top Of The Tangent co-founder)

Dave Schoenstadt. The hour long show was aired at 9:00pm Tuesday

nights. A sample description, from the Tuesday May 14 edition of the

Stanford Daily (clipped above), says

9:00: Flinthill Special- An hour of authentic American folk music, records, tapes, live talent (Dave Schoenstadt)

"Flint Hill Special" was the name of a famous Flatt & Scruggs

bluegrass standard, and in the code of the time, "authentic American

folk music" meant "serious" folk music, like bluegrass or old-time

music, not "popular" sing-alongs like the Kingston Trio.

Ted Claire's deal with the doctors was that he would tape the weekend

Tangent shows, and broadcast some highlights over the air on Tuesday

nights. So the boys and girls in the Stanford dorm who liked folk music

could listen to KZSU and hear what they missed at the Tangent that

weekend. Little did they know that a few years later they'd be seeing

Jerry, Janis and Jorma at the Fillmore, playing many of the same songs

just a little bit louder.

.jpg)