|

| The Sacramento Bee of October 3, 1968, announced that The Turtles had replaced Traffic as the headliner of the concert that included the Grateful Dead and others at the Civic Auditorium on October 5 |

Scholars and fans of the Grateful Dead tend to divide their music into eras. The contours of those eras may be a subject for discussion, but almost everyone would agree that the Dead's music evolved over time, often with a change in emphasis during different periods. While everyone has their own categories, the largest agents for change in the band revolve around the changes in personnel: the arrival, departure and return of Mickey Hart, and the arrival and departure of different keyboard players, too. Yet there was almost another event in 1968 that would have dramatically shaped the Grateful Dead's music: replacing Pigpen with another lead singer.

Let's be clear: it didn't happen. Stockton's Bob Segarini, formerly of the Brogues and the Family Tree, and later of Roxy, The Wackers, The Dudes and a successful solo career as a singer and DJ in Montreal and Toronto, described being asked by Jerry Garcia to consider joining the Grateful Dead as their lead singer. Segarini described this in an interview for the 2007 re-release of the Family Tree's 1968 album. Confusingly, however, he got the date wrong, not surprising after a 38 year gap. Once I sorted out the date issue, however, the entire story makes sense. Segarini said "no," as it happened, which he ruefully called "one more stupid thing I did in my life."

|

| Bob Segarini, from Stockton, CA, lead singer of The Family Tree, around 1968 |

Bob Segarini and the Family Tree opened for the Grateful Dead at the Sacramento Memorial Auditorium on October 5, 1968. In the previous months, Garcia and the Dead had put Bob Weir and Pigpen on notice that they might be replaced. According to McNally, Weir actually believed that he had been fired. No one ever asked Pigpen about it. Over the years I have focused on the Dead's discreet auditions for other guitarists, but here I will focus on the Pigpen question. Segarini and the Family Tree were old Fillmore regulars, so Garcia knew Segarini's music and history. This post will look backwards and forwards at the possibility of Bob Segarini replacing Pigpen, and what that tells us about Garcia's thinking at the end of 1968.

|

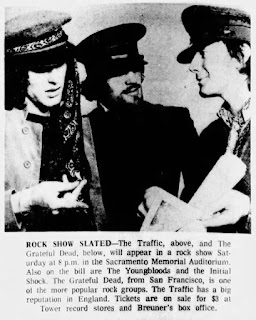

| The Sacramento Bee promoted a picture of Traffic as the headliner for the October 5, 1968 concert with the Grateful Dead, but they were replaced by The Turtles at the last minute |

October 5, 1968 Sacramento Memorial Auditorium, Sacramento, CA: Grateful Dead/The Turtles/Youngbloods/Sanpaku/Initial Shock/Family Tree (Saturday)

On Saturday, October 5, 1968, the Grateful Dead played a show at the Sacramento Memorial Auditorium along with several other bands. The show was only modestly successful, with about 2000 seats filled in a 3600 capacity auditorium. We don't have a tape, but we have a brief review. The Grateful Dead probably played about an hour, since they were just one of six groups on the bill. From careful triangulation, however, we can tell that it was in Sacramento that Jerry Garcia asked Bob Segarini to consider joining the Grateful Dead. The fact that Garcia even asked suggests that the Dead were at a far more critical crossroads at the time than has usually been recognized.

In late summer 1968, probably around August, the Grateful Dead had a meeting in which Bob Weir and Pigpen were told that the band found their musicianship wanting. Even though there is a tape of the meeting, the future success of the Grateful Dead made it in everyone's interests to obscure this rocky moment in the band's history. Weir and Pigpen weren't actually fired, since they continued to perform with the band. By October, however, Weir at least (according to Dennis McNally) thought he had been fired and feared that he would soon be out of the band. The Dead were known to have jammed with Vic Briggs of The Animals, Elvin Bishop and David Nelson, among others, without Bob Weir, so you can't say the idea of replacing Weir wasn't in the air. No one ever talks about replacing Pigpen, however, since his later passing made talking about his possible failings too sad.

From late September 1968 through October 1968 we have only one sure Pigpen sighting with the Grateful Dead. The band played a few gigs during this time and had started recording Aoxomoxoa. Pigpen wasn't involved in recording that album at all, to my knowledge, nor does he play with Mickey and The Hartbeats, and he seems to have skipped at least some gigs. Pigpen sang at the September 20, 1968 show in Berkeley and the September 22 show in San Diego, but he does not appear on the October 12 and 13 Avalon shows. We have no tape or setlist for October 11(Avalon), October 18 (Torrance) or October 19 (Las Vegas) but he sings at the Greek Theater on October 20. You can decide for yourself whether Pigpen thought he was being fired and skipped some gigs, or just that we are simply missing his songs.

We have to assume, by default, that Pigpen was actually at the Sacramento show. Still, the Dead probably only played an hour, as there were six bands on the bill (see below), so perhaps he wasn't. In any case, in the context, consideration of a Pigpen substitute seemed plausible in October 1968, perhaps for the only time in the 1960s.

|

| Mickey and The Hartbeats (booked as "Jerry Garceaaah") on a Matrix flyer, October 8-10, 1968 |

Fall 1968: Was There A Plan?

In Summer '68, Garcia and Phil Lesh apparently felt that Weir and Pigpen were insufficiently committed to the musical advancement that the other four members were undertaking. Songs like "China Cat Sunflower" were entering the repertoire, and the jamming was getting broader and wider, magnified by the double drummers. The Grateful Dead had lined up Tom Constanten to play organ as soon as his Air Force hitch ended in November. TC had apparently jammed with the Dead as early as Fall 1967.

As to another guitarist, the Dead were trying out other guitarists from September through December. Although all parties say now that there were no plans to replace Weir, it rings pretty hollow if you've ever known anybody in a band. If your girlfriend is out of town, and you keep inviting other women to go out dancing with you, are you shopping for a new girlfriend? You can say "no" all you want, but why were you going dancing?

On September 21, 1968, the Dead invited both David Crosby and ex-Animals guitarist Vic Briggs up to San Francisco to jam at Pacific Recording. There's a tape. They took two LA guitarists and invited them up to jam, and Weir wasn't there. At the time, neither was known to have a band (Crosby was already making plans with Stephen Stills and Graham Nash, but it wasn't public). Both players were more advanced than Weir at that stage.

On October 8, 9 and 10, 1968, Garcia, Lesh, Hart and Kreutzmann had played the Matrix as Mickey and The Hartbeats. Elvin Bishop dropped by to jam. Bishop would return for another jam on October 30. Sometime around December, David Nelson was invited to jam with members of the Dead at Pacific Recorders--Bob Weir wasn't there, again--and they tried on "The Eleven." You can't say that the Dead weren't trying out guitarists, not least since they never did anything like this again. They already had a new organist lined up.

There had been an infamous meeting, around August 1968, taped by Owsley, in which the band's unhappiness with Weir and Pigpen was made known. The tape is as much legend as fact. Still, in the excellent Deadcast episode about Pigpen, Jesse Jarnow found a reliable eyewitness (Mike Dolgushkin) who had heard the tape. Interestingly, there was no mention of Pigpen and Weir actually being "fired." The proposal would seem to be that Weir and Pigpen would continue to write songs and record with the Dead, but not be part of the performing unit. Jarnow speculated that this inexplicable proposal only makes sense if you imagine that the Dead were concerned about their status with Warner Brothers, and felt they still needed to include Pig and Weir as signatories to the recording contract.

The Pigpen Deadcast makes another point, however. An eyewitness in Archive comments says that Garcia announced from the stage at one of the October Avalon shows that Pigpen was absent because he was home taking care of his sick girlfriend. His longtime partner, Veronica Barnard (known as Vee) had suffered an aneurysm around this time, and Pigpen was taking time to nurse her back to health. So Pigpen's absence from the Dead in this period may have had more to do with personal choice, and not his status with the band. It seems likely that Pigpen wasn't with the band in Sacramento.

If a full transition was under consideration, however, the band would need another lead singer. Sure, I guess the Dead could consider just having Garcia do all the vocals, but that would not only put a huge strain on Garcia's voice, it would have greatly cut down on the range of songs they could consider. None of the guitarists they had tried out had a significant history as a vocalist. Much later in their careers, both Elvin Bishop and David Nelson would become experienced lead singers, as would David Crosby, but they did not present that way in late 1968. So it makes sense that Garcia was looking around for another lead singer.

|

| The Family Tree opened for Jefferson Airplane at the Fillmore Auditorium on Saturday, April 2 (Quicksilver Messenger Service opened Friday April 1) |

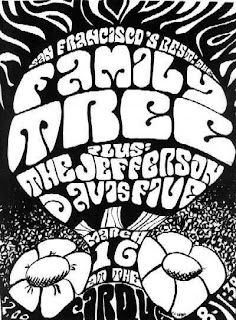

During its existence from 1966-68, the Family Tree only released a single on an obscure label in late 1966, a single on RCA in 1967 and an RCA album around May 1968. They were a successful live band on the West Coast, particularly in Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, but since their recorded output was slim, they remain obscure. The Family Tree name is best known from their presence on Fillmore and Avalon posters from 1966, often opening for Quicksilver Messenger Service. Few people who recognize the name, however, know anything of their music. Bob Segarini had been born and raised in Stockton, in Central California, and he had been in the band Ratz, with Gary Duncan, from nearby Ceres, as early as 1965. Duncan (then known by his birth-name Gary Grubb) would wind up in Quicksilver Messenger Service by 1966. Bob Segarini was thus well-entrenched in the San Francisco music scene from its earliest days.

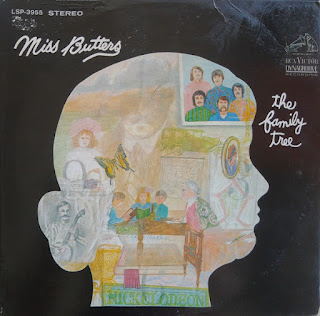

The Family Tree only released two singles, on in 1966 (on Mira) and one on RCA in 1967. They would release the album Miss Butters on RCA in May, 1968, and broke up later that year. With only two singles, an album and some demos, we only have a sketch of what Family Tree sounded like. In general, Segarini found a slot between West Coast folk-rock and Anglo rock and roll. Think of a sweet spot between Buffalo Springfield and The Kinks, and we have at least a hint of the sound of Family Tree.

The Sacramento concert on October 5 was two weeks after the Dead’s jam with Crosby and Briggs, and a few days before the first jam with Bishop at the Matrix. If there was any time Garcia was thinking about a new configuration of the Grateful Dead, it was during this window. The band gets to Sacramento, and Jerry finds his old pal Bob Segarini singing in one of the opening acts, so he hits him up. Before we address the history of Bob Segarini, however, I want to sort out why I am certain that the conversation took place on this date, even though Segarini's own belated account is somewhat different.

|

| Family Tree around 1967, Seagrini in front |

Unpacking The Evidence

I was aware of Bob Segarini's assertion that he had been asked to join the Grateful Dead in 2007, when I read the great liner notes to the Rev-Ola Records cd re-release of the Family Tree's only album, Miss Butters. The album had originally been issued by RCA Records in 1968, and the LP had become a collector's item (I myself had never laid eyes on a vinyl copy, and even though I had been aware of it). Steve Stanley's excellent liner notes discuss the story of Segarini and the Family Tree, and they included this intriguing tale:

During this time [ca 1968-70], Segarani had other career opportunities. He recalls just one example: "In 1969, we were opening the Bitter End West on Santa Monica Boulevard. This was during the period between The Family Tree and Roxy. It was Graham Nash, Rita Coolidge, one of the guitarists from Iron Butterfly, Little Richard's drummer. We were opening the show. The Grateful Dead were the headliners. I'd known Jerry [Garcia] for years, and he said, " Do you want to join the band and be the lead singer? And I said "no, I've already got my own thing going.' One more stupid thing I did in my life; I coulda been in the Grateful Dead."

There were a number of confusing things about this story, which made it difficult to process. In simplest terms, although Segarini was between bands in 1969, the Bitter End West was not open until October 1970, so something was wrong with his timeline. Eventually, however, I was able to unpack the details, which I will explain. I am convinced that Segarini is conflating two very real but separate events:

- Opening for the Grateful Dead and being asked to consider joining the band, in October 1968, and

- Opening for the Grateful Dead in West Hollywood on August 28-29, 1970, at Thee Club, later called The Bitter End West.

I think both these things happened, and Segarini merged them in his mind. He has had a long complicated career, and he was asked 38 years after the fact.

To deal with the second memory first: In 1970, Segarini formed a band called Roxy, who had released a pretty good debut album on Elektra Records in 1969. On the weekend of August 28-29, 1970, Roxy had opened for the acoustic Grateful Dead at a new "showcase" venue called Thee Club. It was a real Hollywood opening, apparently, with all sorts of stars dropping by. By October '70, the venue had changed its name to the Bitter End West (after the famous Greenwich Village folk club). I wrote about the Dead's appearance at Thee Club at great length in another post.

When I realized that Family Tree had opened for the Dead in Sacramento, I put all the pieces together. By October of 1968, Family Tree had all but fallen apart, but they had still opened for the Grateful Dead. The next time Segarini would open for the Dead was at Thee Club, and I am asserting that he just merged the two events.

|

| Animals guitarist Vic Briggs (right), jamming with a friend, probably May 1968 |

What Might Have Been

I don't want to go too far for down the counterfactual road, but let's at least think about a new-look late 1968 Grateful Dead:

- Garcia, Lesh, Hart and Kreutzmann

- Another guitarist to duel with Garcia (Vic Briggs, Elvin Bishop, David Nelson or who knows?)

- Tom Constanten on organ

- Bob Segarini on lead and harmony vocals, and maybe some rhythm guitar

Lots of fine 60s bands had significant personnel changes, and they had a wide variety of outcomes, many, though not all, quite favorable There's no reason that the Alterna-Grateful Dead couldn't have risen to the heights of the one in our timeline, but I'll leave that speculation to you. Now, even if Segarini had said "yes," it was no guarantee that he would have actually ended up replacing Pigpen, and we can imagine scenarios in which Weir remains but Segarini also joins, but we'll leave it to our imagination to consider what that band might have sounded like.

|

| Bob Segarini, with his band The Dudes, late 1970s |

Who Is Bob Segarini?

Bob Segarini was raised in Stockton, CA. At about age 16, he dropped out of high school to become a full-time musician. In 1965, he was in a band called The Ratz with guitarist Gary Grubb, from the tiny town of Ceres, near Modesto. The Ratz opened for the Rolling Stones on December 4, 1965 in San Jose. Grubb went on to form The Brogues, and later Quicksilver Messenger Service, using the name Gary Duncan.

Segarini, meanwhile, had formed The Family Tree in early 1966. Members included organist Micheal Olsen and ex-Brogues bassist Bill Whittington, and drummer Newman Davis. The Family Tree played many early gigs at the Fillmore and elsewhere with Quicksvilver Messenger Service. So Segarini had been a regular on the Fillmore scene since its inception. Within a few months, the Family Tree had evolved. Whittington and Mike Olsen left--Olsen becoming famous using the name Lee Michaels--and Segarini was joined by bassist Kootch Trochim, guitarist Mike Dure, organist Jimmy DeCocq and drummer Van Slatter. Initially, Family Tree had signed with tiny Mira Records.

The "Fillmore Scene," such as it was on the West Coast, also existed in parallel with a pre-existing teen circuit with its initial roots in the Pacific Northwest. Bands like the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver only dabbled in that circuit, just playing the occasional high school prom, but there was a lot of money for bands playing the typical teen dance halls. Family Tree did very well from Sacramento through Oregon. They had a regional hit in early 1967 with their only Mira single "Prince Of Dreams." Segarini recalls buying a new 1966 Jaguar XKE with cash from all the money the Family Tree made playing the Northwest.

|

| The view from the front yard of Bob Segarini and Roxy's house "Cold Red," outside of Stockton in 1969 |

Segarini has a wonderful blog called Don't Believe A Word I Say, which you can read for yourself. It's very entertaining, and very long (Segarini says it is 1.8 million words and I believe him). I did extract this Grateful Dead story, written in 2012. The timeline seems somewhat garbled--plainly Mr Owsley's fault--but this passage about the house his band was living in 1969, just outside of Stockton, includes a discussion of where they got their acid. From the source, as it happens. Clearly, Segarini was no outsider.

I had come into possession of the acid by way of an acquaintance we had met through The Grateful Dead, whom I had gotten to know during the Family Tree days at the Fillmore and Avalon. Owsley, (Augustus Owsley Stanley, who occasionally went by the name ‘Robert Owsley’ for some strange reason), was not only a fine chemist, but one of the most advanced sound technicians of the day. He spent time both before and after serving time for drugs, as an investor in the Dead, as well as their soundman. At one point, when Roxy was living in L.A, and the Dead were in a rented house there while they were recording, we all went to their place for Chinese food, and found the entire house full of sound equipment and a shitload of big Voice of Theater speakers. Very cool…you either had to sit on the floor and eat, or stand at one of the speaker cabinets and eat. It was so…exotic!

|

| Miss Butters, the only album by The Family Tree, released on RCA in May 1968 |

By 1968, an album on Mira hadn't materialized, but RCA had noticed the Family Tree's regional hit, and signed the band to a contract. RCA had been hugely successful with the Jefferson Airplane, so they must have been looking to capitalize on new young bands from the West Coast. The Family Tree recorded Miss Butters with RCA staff producer Rick Jarrard, who had also produced the Airplane. Miss Butters had Beatles-like pop overtones, probably somewhat at odds with the more rocking sound of Family Tree in concert.

Miss Butters was released in May 1968, but it had no hit single and largely disappeared without a trace. The Family Tree ground to a halt. By October 1968 Kootch Trochim was already playing bass for another Sacramento band (Sanpaku), and the Sacramento Civic show must have been one of Family Tree's last gigs under that name. By early 1969, Segarini and others played under the name Asmodeus, but they didn't play much. Segarini would go on to form Roxy with guitarist Randy Bishop (for more about Segarini's later career, see below). Roxy, too, opened for the Dead at Thee Experience in 1970, but as noted, Segarini seems to have merged the events in the telling.

|

| The September 29 Sacramento Bee listed upcoming concerts. Traffic was the scheduled headliner for Saturday, October 5 (replaced by The Turtles) |

Concert Report: October 5, 1968 Sacramento Memorial Auditorium, Sacramento, CA

The Sacramento show was promoted by Whitey Davis. Davis had been one of Chet Helms' lieutenants at the Avalon in late 66, and had moved up to Oregon. Davis had been the co-proprietor of the infamous Crystal Ballroom in Portland. By Summer '68, however, the Crystal had folded, and Davis turned up in Sacramento. He started booking shows at a place called The Sound Factory, which was supposed to be Sacramento's version of the Fillmore, and working with KZAP-fm, the local underground rock radio station. He also managed the band Sanpaku. The Sacramento Memorial Auditorium was the biggest venue in town, with 3600 seats.

Initially, Traffic had been booked as the headliners. They had been scheduled to open for Cream at the Oakland Coliseum (October 4), and play the ill-fated "San Francisco Pop Festival" outside of Stanford University on October 6. The band had just released their great second album, Traffic, with "Feelin' Alright" and many other classics. Dave Mason abruptly quit the band, however, and all dates were canceled. Instead of Traffic, The Collectors opened for Cream, the San Francisco Pop Festival was moved from Stanford to Pleasanton, and The Turtles replaced Traffic in Sacramento. The Grateful Dead were bumped up to headliners. The Turtles, regardless of their bubblegum-pop hits, were actually a terrific folk-rock group.

With six bands on the bill, every band must have played short sets. I don't know what advantage Whitey Davis would have seen in booking so many bands. Only 2000 people attended, so it can't have been a huge success. We do have one brief review, from Mick Martin in the Sacramento underground paper Pony Express:

In Sacramento, The GRATEFUL DEAD, TURTLES, YOUNGBLOODS, INITIAL SHOCK, SANPAKU, and FAMILY TREE played to a surprisingly small crowd of 2,000. [Memorial Auditorium, 10/5/68] The TURTLES were funny and entertaining. They were a release from the intensely musically innovative atmosphere. Mark Volmann is a comedian, in the truest sense of the word.

The DEAD, INITIAL SHOCK, and SANPAKU were the musical highpoints of the evening. SANPAKU's hornmen are so beautiful, their solos are always different, and yet they build to a completely emotional climax. Their original material is well arranged and worth repeated listens.

INITIAL SHOCK and the DEAD were better than ever and twice as groovy. Both groups always provide me with the feeling that I have heard something worthwhile, and on this night I felt they did exceptional jobs. YOUNGBLOODS were nice, and FAMILY TREE shows promise. It was an enjoyable evening, but I can't wait for Sacramento to get it together and support promoters like Whitey Davis, who really cares about music.

This brief review does not indicate whether Pigpen performed. If so, it would have been the only sighting of him for 30 days. If he wasn't present, it might also have made it easier for Garcia to chat openly with Segarini about replacing him.

Segarini took a pass. Ultimately, Pigpen returned. Bob Weir never left. Bob Segarini went to LA, then Northern California, then Montreal, then Toronto and had a pretty lively career in the music business.

Coulda been different. Wasn't. So it goes.

Appendix: Bob Segarini Career Overview

Bob Segarini may not be a major figure, but he's a pretty good rock and roller with a diverse career, and it's still going on. I have sketched out a few highlights here, but this list isn't anywhere near the entire story. For more about Segarini, see his own blog Don't Believe A Word. For a starting point on his extensive catalog, I would recommend Wackering Heights, the 1971 debut album of The Wackers.

The Us

Bob Segarini first surfaces on tape with The Us, recorded by Autumn Records in Fall '65. San Francisco-based Autumn had scored a hit with The Beau Brummels, and was recording emerging rock bands around the Bay Area, including The Great Society (with Grace Slick) and The Emergency Crew (later to change their names to The Warlocks, and then to something else).

The track "How Can I Tell Her, " written by Segarini, was produced by staff producer Sylvester Stewart, later better known as Sly Stone. I'm not certain if the track was actually released as a single. Segarini was apparently credited as "Cylus Prole," possibly because he wasn't a legal adult yet. The rest of the band was bassist Varsh Hammel, guitarists Jock Ellis and Rueben Bettencourt and drummer Frank Lupica. Lupica, in another instance of convergence, created his "Cosmic Beam" which was the direct inspiration for the instrument built by Dan Healy and Mickey Hart.

The Ratz

The Ratz were from Stockton, and briefly featured Ceres, CA guitarist Gary Grubb along with Segarini. Grubb had left The Ratz by the time they opened for the Rolling Stones at the San Jose Civic Auditorium on December 4, 1965.

Grubb would join a Merced band called The Brogues, who were popular in San Jose and the Central Valley, and released a few singles. Grubb and Brogues drummer Greg Elmore had met guitarists John Cippolina and Jim Murray at a Family Dog event at Longshoreman's Hall in October '65. The Brogues ended up breaking up because some members got drafted into the military, so Grubb and Elmore formed a band with their two Marin friends. By 1966, the band was named Quicksilver Messenger Service and Grubb was using the name Gary Duncan.

|

| The

Cirque, Hillsboro, OR March 16, 1968. San Francisco's Best, The Family

Tree plus The Jefferson Davis Five (Hillsboro is West of Portland) |

Family Tree

The Family Tree was founded in early 1966 by Segarini and ex-Brogues bassist Bill Whittington. Also in the initial lineup of Family Tree were drummer Newman Davis and organist Mike Olsen (formerly of the Joel Scott Hill Trio). The Family Tree played both the early Fillmore circuit and the "teen circuit" in Northern California and the Pacific Northwest. Segarini knew Gary (Grubb) Duncan, of course, so Family Tree was in on the Fillmore from the very beginning. It's not clear how Segarini had met Jerry Garcia, but it doesn't matter: the San Francisco psychedelic music scene was tiny, with only a few dozen working musicians, and everyone knew each other.

Family Tree had started to attract attention later in 1966. By this time, Mike Olsen had left for a solo career under the name Lee Michaels (Lee's first drummer was Frank Lupica, incidentally). Jim DeCocq joined on keyboards, Vann Slater came in on drums, Danny "Kootch" Trochim replaced Whittington on bass and Mike Dure was added on lead guitar. The Family Tree was signed by Los Angeles based Mira Records, releasing the single "Prince Of Dreams" on Mira in September '66. Additional tracks were recorded for a prospective album, but Mira fell apart.

Family Tree was increasingly successful on the California/Oregon live circuit, however, and they were picked up by RCA. A single was released by RCA in 1967, and the band recorded the album Miss Butters under the direction of staff producer Rick Jarrard. The rocking side of Family Tree can be heard on the Mira demos from '67, but the RCA album emphasized the poppier side of Segarini's work. Now, to be clear, Segarini had written all the songs and was very much into Beatles-style pop music, so RCA wasn't undermining the band, but all the traces suggest Family Tree rocked much harder in concert than Miss Butters implies.

Miss Butters was released in May 1968, but made no headway on the charts. Family Tree soldiered on, but ultimately fell apart. The October booking in Sacramento seems to be one of the last for Family Tree. By this time, Kootch Trochim was playing bass for the Sacramento band Sanpaku (also on the bill), and I don't know who else was even in Family Tree by then.

Family Tree discography

Sep 1966 45: Mira Records "Prince Of Dreams"/"Live Your Own Life"

1967 45: RCA Records "Do You Have The Time"/"Keepin A Secret"

May 1968 LP: RCA Records Miss Butters

|

| A Berkeley Barb ad for Berkeley's New Orleans House, February 1969. Sea Train had recently been the reformed Blues Project. The Steve Miller playing the next week is the organist from the band Linn County (and later Elvin Bishop), not the better-known guitarist. A.B. Skhy featured Howard Wales. |

Asmodeus

I don't know who was in Asmodeus save for Bob Segarini. They apparently played around in early 1969.

|

| Roxy's only LP, released on Elektra Records in 1969 |

Roxy

Roxy formed later in 1969, with Jimmy DeCocq (now lead guitar), Randy Bishop (bass, guitar, vocals), James Morris (keyboards) and John McDonald (drums). They released one album on Elektra in 1969. Roxy had a more upbeat sound than Miss Butters. They lasted until late 1970, and opened for the Grateful Dead at least twice. Roxy opened for the Dead in Phoenix on March 8, 1970, and then for the acoustic Grateful Dead at the Thee Club in August 1970 (Thee Club changed its name shortly afterwards to the Bitter End West).

The Wackers

In late 1970, Segarini and Bishop abandoned Roxy, who had ground to a halt. They moved themselves up to the far-Northern California outpost of Eureka, CA. For those not familiar with the geography, Eureka is 270 miles North of San Francisco, and though near to the Oregon border, it is still 400 miles South of Portland. It was (and remains) completely detached from the California music scene. Segarini knew the region from his success with Family Tree, but moving to Eureka wasn't an obvious career move.

Segarini and Bishop formed The Wackers, along with drummer Earnie Earnshaw, Michael Stull (keyboards, guitar and vocals) and returning bassist Kootch Trochim. Wackering Heights, the bands first album on Elektra, had great harmonies in the popular vein of Crosby, Stills and Nash, but propelled by short, catchy songs with a beat.

In 1972, after the band's second album Hot Wacks, The Wackers relocated to Montreal, Quebec. They drove there in an old VW bus. Elektra released their third album, Shredder later in 1972. The Wackers, stayed in Montreal, building up a following in Canada.

|

| The Dudes 1975 Columbia Records album |

The Dudes

The Wackers had some personnel changes after Shredder, including some Canadian musicians. By 1974, The Wackers were gone, and Segarini had formed The Dudes, with Kootch on bass and some Canadian players. In 1975, Columbia released The Dudes debut We're No Angels, but the band fell apart.

|

| Gotta Have Pop, Bob Segarini's first solo album, released on Bomb Records in 1978 |

Gotta Have Pop-Bob Segarini

Since The Dudes fell apart, Segarini went solo. His first album Gotta Have Pop was released in 1978. He went on to have an extensive solo career in Canada, which I will not attempt to summarize here.

In 1982, Segarini began a successful career as a dj at the Toronto fm station CHUM. As near as I can tell, he is better known as a radio personality in Canada than as a singer, though of course the two careers are merged.